Image: Shutterstock.

Apple and the satellite-based broadband service Starlink each recently took steps to address new research into the potential security and privacy implications of how their services geo-locate devices. Researchers from the University of Maryland say they relied on publicly available data from Apple to track the location of billions of devices globally — including non-Apple devices like Starlink systems — and found they could use this data to monitor the destruction of Gaza, as well as the movements and in many cases identities of Russian and Ukrainian troops.

At issue is the way that Apple collects and publicly shares information about the precise location of all Wi-Fi access points seen by its devices. Apple collects this location data to give Apple devices a crowdsourced, low-power alternative to constantly requesting global positioning system (GPS) coordinates.

Both Apple and Google operate their own Wi-Fi-based Positioning Systems (WPS) that obtain certain hardware identifiers from all wireless access points that come within range of their mobile devices. Both record the Media Access Control (MAC) address that a Wi-FI access point uses, known as a Basic Service Set Identifier or BSSID.

Periodically, Apple and Google mobile devices will forward their locations — by querying GPS and/or by using cellular towers as landmarks — along with any nearby BSSIDs. This combination of data allows Apple and Google devices to figure out where they are within a few feet or meters, and it’s what allows your mobile phone to continue displaying your planned route even when the device can’t get a fix on GPS.

With Google’s WPS, a wireless device submits a list of nearby Wi-Fi access point BSSIDs and their signal strengths — via an application programming interface (API) request to Google — whose WPS responds with the device’s computed position. Google’s WPS requires at least two BSSIDs to calculate a device’s approximate position.

Apple’s WPS also accepts a list of nearby BSSIDs, but instead of computing the device’s location based off the set of observed access points and their received signal strengths and then reporting that result to the user, Apple’s API will return return the geolocations of up to 400 hundred more BSSIDs that are nearby the one requested. It then uses approximately eight of those BSSIDs to work out the user’s location based on known landmarks.

In essence, Google’s WPS computes the user’s location and shares it with the device. Apple’s WPS gives its devices a large enough amount of data about the location of known access points in the area that the devices can do that estimation on their own.

That’s according to two researchers at the University of Maryland, who said they theorized they could use the verbosity of Apple’s API to map the movement of individual devices into and out of virtually any defined area of the world. The UMD pair said they spent a month early in their research continuously querying the API, asking it for the location of more than a billion BSSIDs generated at random.

They learned that while only about three million of those randomly generated BSSIDs were known to Apple’s Wi-Fi geolocation API, Apple also returned an additional 488 million BSSID locations already stored in its WPS from other lookups.

UMD Associate Professor David Levin and Ph.D student Erik Rye found they could mostly avoid requesting unallocated BSSIDs by consulting the list of BSSID ranges assigned to specific device manufacturers. That list is maintained by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), which is also sponsoring the privacy and security conference where Rye is slated to present the UMD research later today.

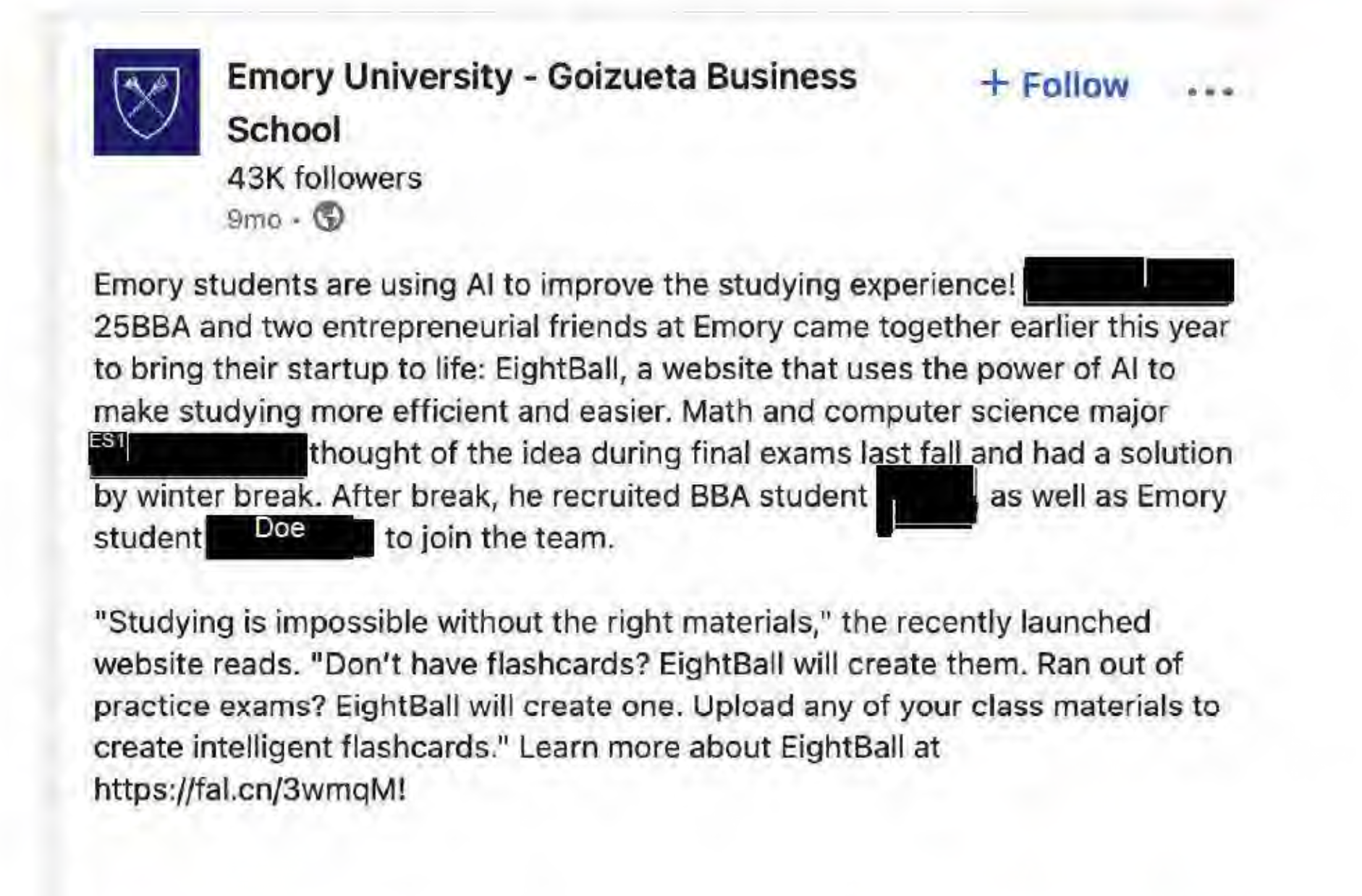

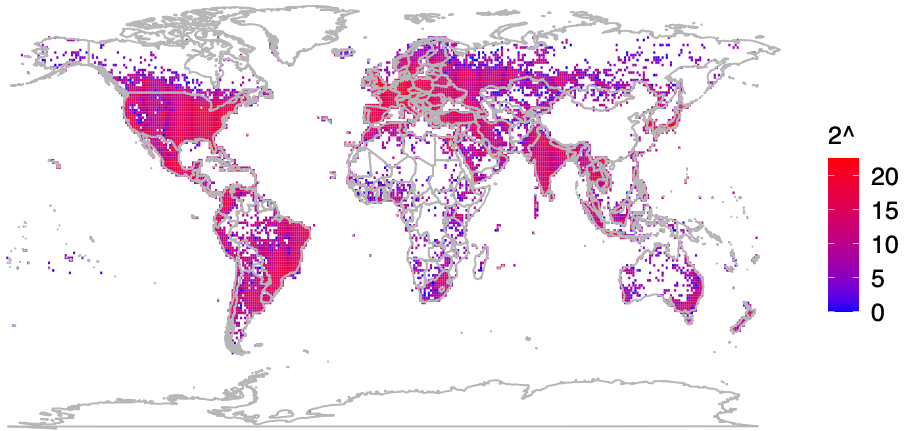

Plotting the locations returned by Apple’s WPS between November 2022 and November 2023, Levin and Rye saw they had a near global view of the locations tied to more than two billion Wi-Fi access points. The map showed geolocated access points in nearly every corner of the globe, apart from almost the entirety of China, vast stretches of desert wilderness in central Australia and Africa, and deep in the rainforests of South America.

A “heatmap” of BSSIDs the UMD team said they discovered by guessing randomly at BSSIDs.

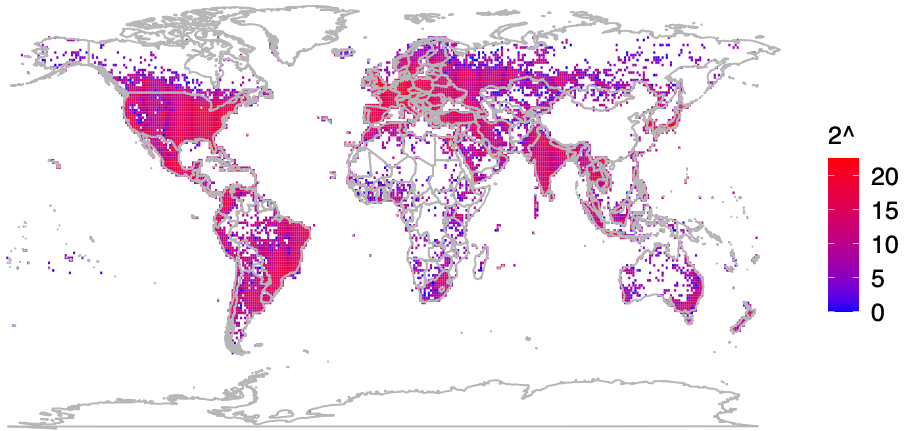

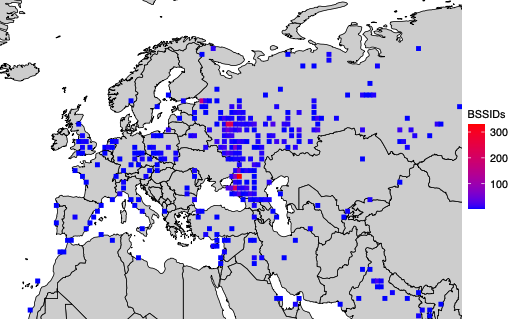

The researchers said that by zeroing in on or “geofencing” other smaller regions indexed by Apple’s location API, they could monitor how Wi-Fi access points moved over time. Why might that be a big deal? They found that by geofencing active conflict zones in Ukraine, they were able to determine the location and movement of Starlink devices used by both Ukrainian and Russian forces.

The reason they were able to do that is that each Starlink terminal — the dish and associated hardware that allows a Starlink customer to receive Internet service from a constellation of orbiting Starlink satellites — includes its own Wi-Fi access point, whose location is going to be automatically indexed by any nearby Apple devices that have location services enabled.

A heatmap of Starlink routers in Ukraine. Image: UMD.

The University of Maryland team geo-fenced various conflict zones in Ukraine, and identified at least 3,722 Starlink terminals geolocated in Ukraine.

“We find what appear to be personal devices being brought by military personnel into war zones, exposing pre-deployment sites and military positions,” the researchers wrote. “Our results also show individuals who have left Ukraine to a wide range of countries, validating public reports of where Ukrainian refugees have resettled.”

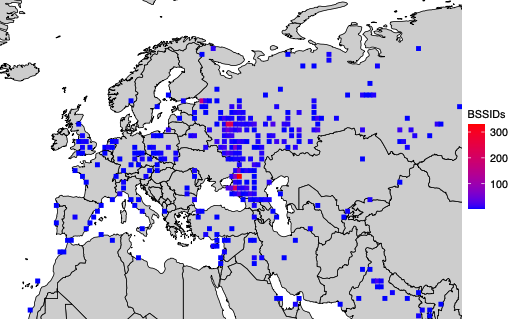

In an interview with KrebsOnSecurity, the UMD team said they found that in addition to exposing Russian troop pre-deployment sites, the location data made it easy to see where devices in contested regions originated from.

“This includes residential addresses throughout the world,” Levin said. “We even believe we can identify people who have joined the Ukraine Foreign Legion.”

A simplified map of where BSSIDs that enter the Donbas and Crimea regions of Ukraine originate. Image: UMD.

Levin and Rye said they shared their findings with Starlink in March 2024, which said it began shipping software updates in 2023 that force Starlink access points to randomize their BSSIDs.

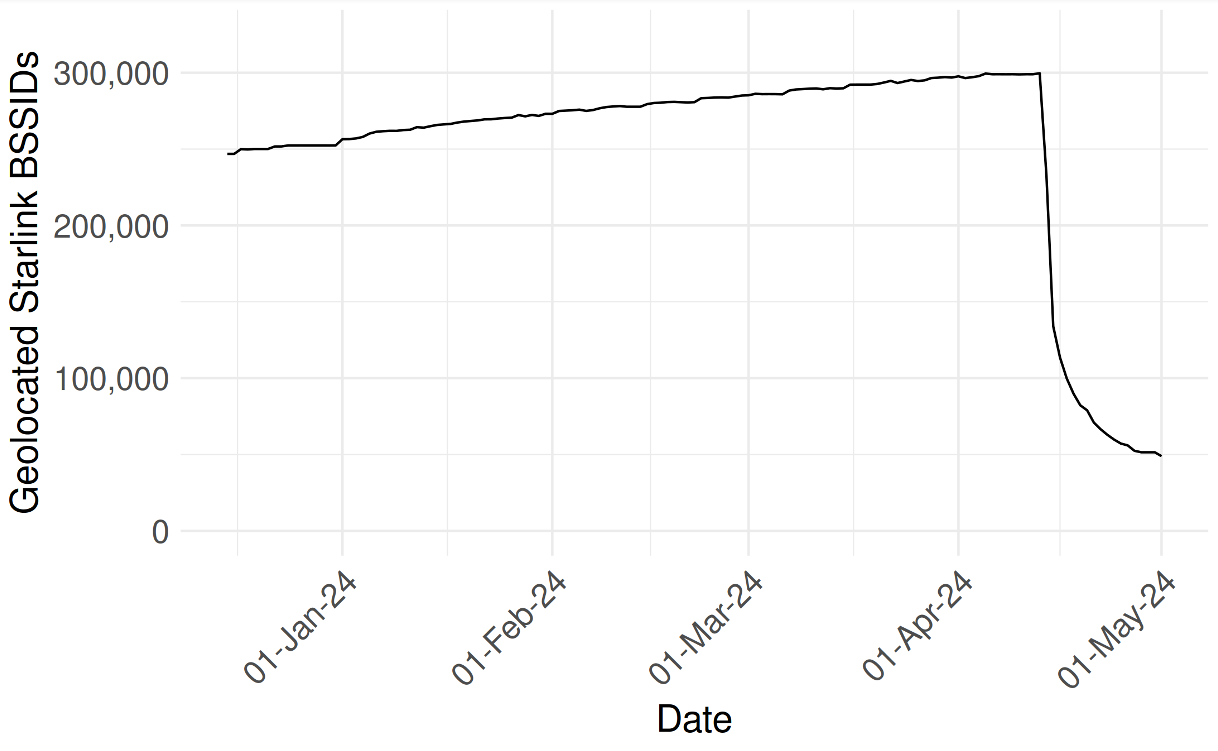

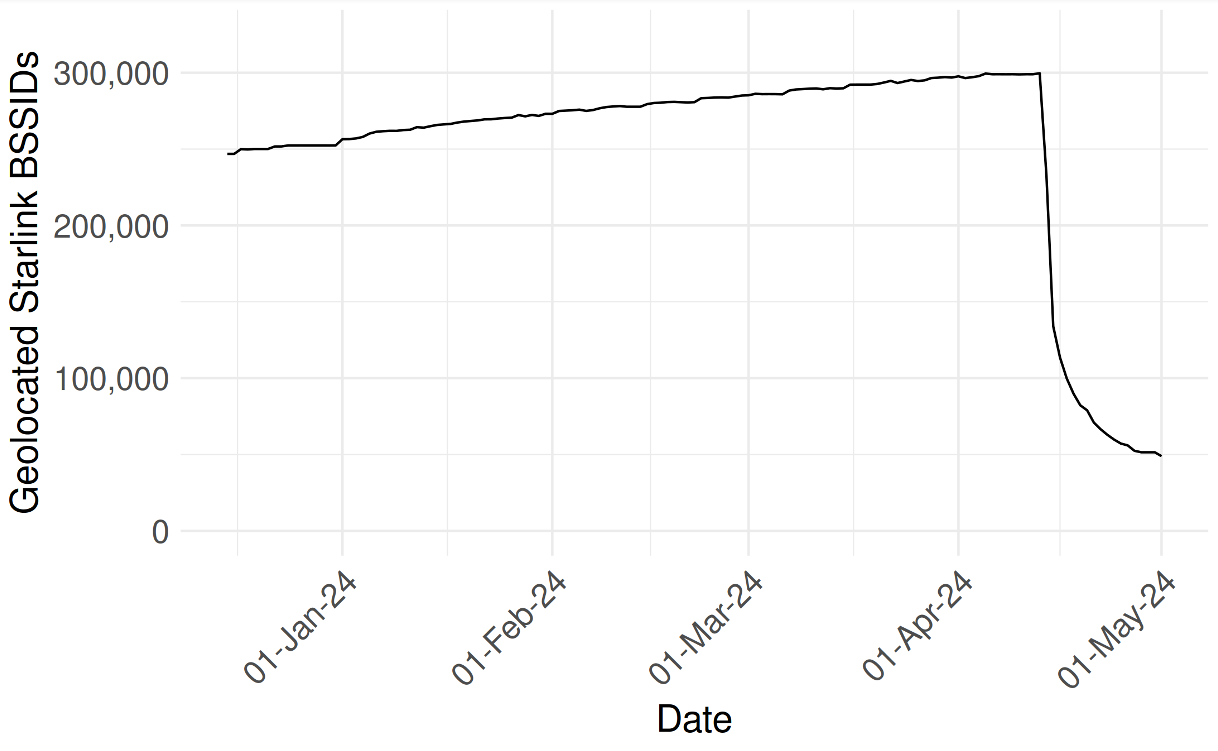

Starlink’s parent SpaceX did not respond to requests for comment. But the researchers shared a graphic they said was created from their Starlink BSSID monitoring data, which shows that just in the past month there was a substantial drop in the number of Starlink devices that were geo-locatable using Apple’s API.

UMD researchers shared this graphic, which shows their ability to monitor the location and movement of Starlink devices by BSSID dropped precipitously in the past month.

They also shared a written statement they received from Starlink, which acknowledged that Starlink User Terminal routers originally used a static BSSID/MAC:

“In early 2023 a software update was released that randomized the main router BSSID,” the statement reads. “Subsequent software releases have included randomization of the BSSID of WiFi repeaters associated with the main router. Software updates that include the repeater randomization functionality are currently being deployed fleet-wide on a region-by-region basis. We believe the data outlined in your paper is based on Starlink main routers and or repeaters that were queried prior to receiving these randomization updates.”

The researchers also focused their geofencing on the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, and were able to track the migration and disappearance of devices throughout the Gaza Strip as Israeli forces cut power to the country and bombing campaigns knocked out key infrastructure.

“As time progressed, the number of Gazan BSSIDs that are geolocatable continued to decline,” they wrote. “By the end of the month, only 28% of the original BSSIDs were still found in the Apple WPS.”

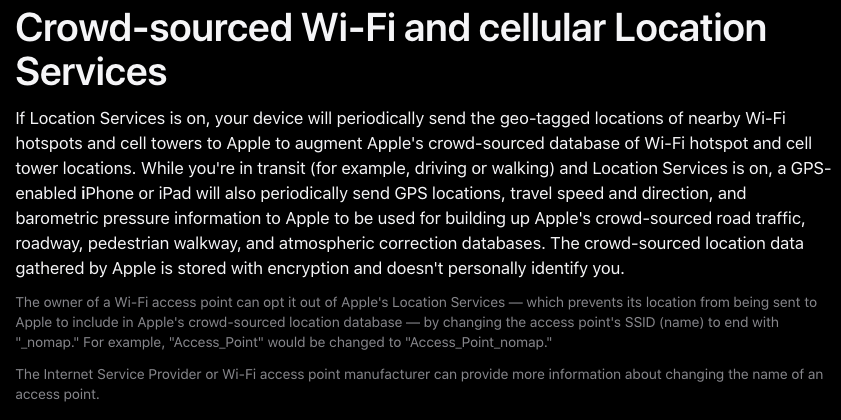

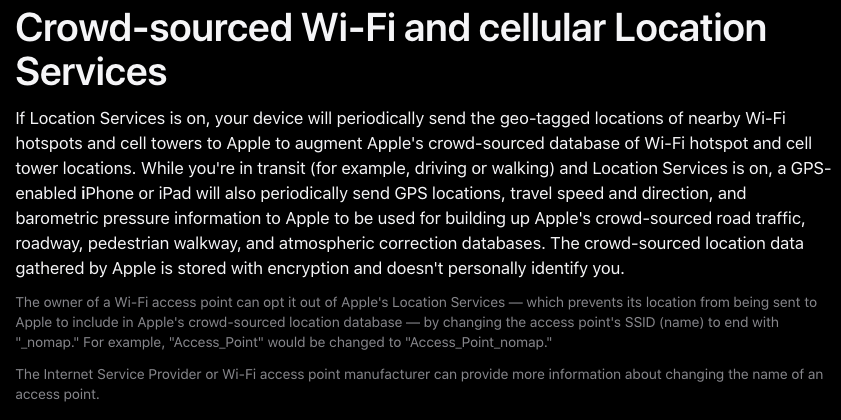

Apple did not respond to requests for comment. But in late March 2024, Apple quietly tweaked its privacy policy, allowing people to opt out of having the location of their wireless access points collected and shared by Apple — by appending “_nomap” to the end of the Wi-Fi access point’s name (SSID).

Apple updated its privacy and location services policy in March 2024 to allow people to opt out of having their Wi-Fi access point indexed by its service, by appending “_nomap” to the network’s name.

Rye said Apple’s response addressed the most depressing aspect of their research: That there was previously no way for anyone to opt out of this data collection.

“You may not have Apple products, but if you have an access point and someone near you owns an Apple device, your BSSID will be in [Apple’s] database,” he said. “What’s important to note here is that every access point is being tracked, without opting in, whether they run an Apple device or not. Only after we disclosed this to Apple have they added the ability for people to opt out.”

The researchers said they hope Apple will consider additional safeguards, such as proactive ways to limit abuses of its location API.

“It’s a good first step,” Levin said of Apple’s privacy update in March. “But this data represents a really serious privacy vulnerability. I would hope Apple would put further restrictions on the use of its API, like rate-limiting these queries to keep people from accumulating massive amounts of data like we did.”

The UMD researchers said they omitted certain details from their research to protect the users they were able to track, noting that the methods they used could present risks for those fleeing abusive relationships or stalkers.

“We observe routers move between cities and countries, potentially representing their owner’s relocation or a business transaction between an old and new owner,” they wrote. “While there is not necessarily a 1-to-1 relationship between Wi-Fi routers and users, home routers typically only have several. If these users are vulnerable populations, such as those fleeing intimate partner violence or a stalker, their router simply being online can disclose their new location.”

The researchers said Wi-Fi access points that can be created using a mobile device’s built-in cellular modem do not create a location privacy risk for their users because mobile phone hotspots will choose a random BSSID when activated.

“Modern Android and iOS devices will choose a random BSSID when you go into hotspot mode,” he said. “Hotspots are already implementing the strongest recommendations for privacy protections. It’s other types of devices that don’t do that.”

For example, they discovered that certain commonly used travel routers compound the potential privacy risks.

“Because travel routers are frequently used on campers or boats, we see a significant number of them move between campgrounds, RV parks, and marinas,” the UMD duo wrote. “They are used by vacationers who move between residential dwellings and hotels. We have evidence of their use by military members as they deploy from their homes and bases to war zones.”

A copy of the UMD research is available here (PDF).