NPR, the great bastion of old-school audio journalism, is a mess. But as someone who loves NPR, built my career there, and once aspired to stay forever, I say with sadness that it has been for a long time.

This might be news to those who tune out the circular firing squad of institutional media whiners. But my former NPR colleague Uri Berliner, one of the organization’s (as of now) senior editors, set off a firestorm by publishing a commentary that essentially blamed “wokeness” and Democratic partisanship for the apparent loss of confidence in the once-unimpeachable institution. (This morning, news broke that Uri has been suspended by NPR for violating a policy about “outside work,” and informed that he’d be fired for any more infractions.) The essay, published by Bari Weiss’ the Free Press, blew up certain corners of X and various Facebook feeds, and was gleefully lapped up by conservatives who’ve been fighting to defund NPR and public broadcasting for a generation.

It was a longtime fear at NPR that some scandal or mess that the network had hoped to contain within its headquarters, lovingly referred to as the “mother ship” by nippers and ex-nippers everywhere, would find its way to the outside world, where the organization’s very real, powerful enemies could exploit it. In fact, this is happening right now; Christopher Rufo, a conservative writer and fellow at the Manhattan Institute, has launched a campaign against NPR’s new CEO Katherine Maher, accusing her of liberal bias based on old tweets. Those kinds of threats reinforce an in-the-trenches camaraderie at NPR. It has also been used to quash internal criticism. I guess Uri’s piece proves that that strategy doesn’t work anymore.

Uri started at NPR in 1999. I started in 1997 in the audience research department as an administrative assistant. Because I was what we called “a back-seat baby,” someone who’d grown up being force-fed a steady diet of NPR from car radios and in the home by crunchy granola parents, I had spent the past several months before my college graduation searching the organization’s rudimentary website, desperate to find anything that I was qualified to do. A year later, I maneuvered into the news division as the editorial assistant to senior correspondent Daniel Schorr and one of the “Murrow Boys,” protégés of CBS Radio legend and Good Night, and Good Luck hero Edward R. Murrow.

After a stint at Salon from 1999 to 2001, I landed back at NPR. Everyone did. It was an institutional joke that people who left for other jobs would find their way back, because the place was irresistible. And it kind of was. So many people there were/are brilliant, kind, funny, interesting, and dedicated to public service. Aside from my family, I found most of the people I like, love, and care about while I was working at NPR.

So when Uri’s piece started popping up on my timeline last week, it felt like hearing a loud, ugly family argument break out in the room next door: I wanted to pretend as if it weren’t happening; I wanted people to shut up. But if they were going to shout, I at least wanted them to tell the whole story.

And that story is that NPR has been both a beacon of thoughtful, engaging, and fair journalism for decades, and a rickety organizational shit show for almost as long. If former CEO John Lansing—the big bad of Uri’s piece—failed to fix it, or somehow made it worse, that’s a failure he shared with almost every NPR leader before him. But if, as Uri charges (albeit in a negative way), Lansing genuinely managed to break the network loose from the grasp of self-righteous white liberal identity politics, even in an imperfect way, that would surprise the hell out of me. Especially given the well-reported exodus of top journalists of color, and the loss of a diverse group of journalists during last year’s podcast layoffs.

It did take a kind of courage for Uri to publicly criticize the organization. But it also took a lot of the wrong type of nerve. His argument is a demonstration of contemporary journalism at its worst, in which inconvenient facts and obvious questions were ignored, and the facts that could be shaped to serve the preferred argument were inflated in importance.

Take a step into the way-back machine to 2011, Uri’s so-called golden age. That’s the year when senior members of the development team fell for a scam set up by professional provocateur James O’Keefe. The aftermath took them out and toppled then–CEO and President Vivian Schiller. It came months after the ill-timed, clumsy firing of Juan Williams, which led to senior vice president of news Ellen Weiss resigning under pressure.

Uri also leapfrogs over a long list of contemporary fuckups and questionable calls that could explain the growing public distrust that concerns him. There were questions about NPR legal affairs correspondent Nina Totenberg’s personal relationship with Ruth Bader Ginsburg compromising her reporting; the departure of news chief Mike Oreskes, and other prominent men in the newsroom‚ after a wave of sexual harassment charges; the exposure of systematic exploitation of NPR’s temporary workforce. And those are just the public problems.

Behind the scenes and stretching back into the “golden age,” there were major strategic errors that seriously damaged the network’s prospects. The founding producer of The Daily at the New York Times was Theo Balcomb, a senior producer at All Things Considered who couldn’t get enough support to launch a morning news podcast inside NPR. There was the “Flat is the new growth” mantra that reigned for a few years after the network decided that a multimedia future meant shrugging off softness in listener numbers for core shows. Then there was the time in the late aughts when leadership decided that podcasting wasn’t going to amount to much, and so pumped the brakes on early efforts. Though the failure of imagination started earlier; the first big blunder I saw was in the late 1990s, when the network failed to lock in a deal with a little show called This American Life.

Uri’s account of the deliberate effort to undermine Trump up to and after his election is also bewilderingly incomplete, inaccurate, and skewed. For most of 2016, many NPR journalists warned newsroom leadership that we weren’t taking Trump and the possibility of his winning seriously enough. But top editors dismissed the chance of a Trump win repeatedly, declaring that Americans would be revolted by this or that outrageous thing he’d said or done. I remember one editorial meeting where a white newsroom leader said that Trump’s strong poll numbers wouldn’t survive his being exposed as a racist. When a journalist of color asked whether his numbers could be rising because of his racism, the comment was met with silence. In another meeting, I and a couple of other editorial leaders were encouraged to make sure that any coverage of a Trump lie was matched with a story about a lie from Hillary Clinton. Another colleague asked what to do if one candidate just lied more than the other. Another silent response.

I left NPR in the early fall of 2016, but when I came back to work on Morning Edition about a year later, I saw NO trace of the anti-Trump editorial machine that Uri references. On the contrary, people were at pains to find a way to cover Trump’s voters and his administration fairly. We went full-bore on “diner guy in a trucker hat” coverage and adopted the “alt-right” label to describe people who could accurately be called racists. The network had a reflexive need to stay on good terms with people in power, and journalists who had contacts within the administration were encouraged to pursue those bookings.

We regularly set up live interviews with Republican officials and Trump surrogates. But it was tough because NPR always loved guests who would be insightful, honest, and—perhaps above all—polite. There were plenty of people who’d for years fit that description across the partisan divide in official Washington, but they were scarce in the Trump administration. We changed the format of live political interviews, adding what we called a “level-set.” That would be three-ish minutes after a conversation with a political operative or elected official when a host and NPR reporter would try to fact-check what had just been said.

Maybe the biggest head-scratcher for me in Uri’s argument is how it frames the lack of pursuit of the Hunter Biden laptop story as driven exclusively by politics. Uri said there was no follow-through because “the timeless journalistic instinct of following a hot story lead was being squelched.” In fairness, I left NPR for good in the spring of 2020, so I wasn’t there for this story arc. And the inappropriate statement, from a loose-lipped editor, that “it was good we weren’t following the laptop story because it could help Trump” sounds on-brand. But that killer instinct was regularly beat out of NPR journalists, regardless of the political mood or the president.

People pitched good stories in our meetings all the time that were dismissed as insubstantial, or not interesting, or not important enough, only for them to appear days or weeks later in the New York Times or the Washington Post. And only then, NPR leaders would want reporters to jump on it.

There were several reasons why good pitches died. The pitcher wasn’t high enough in the editorial landscape to be taken seriously. The resources were scarce because we were top-heavy and spread thin, trying to cover the country and the world, far beyond electoral politics. We didn’t have enough reporters or the right reporters on whatever beat to cover the story properly. Correspondents, reporters, and desks could be very territorial, and if this one specific reporter wasn’t able to do a story—because they were covering something else, or on leave, or didn’t feel like it—the piece frequently died. If reporting on an issue or story had already been done by an NPR reporter, a pitch could get smothered. That’s even if the original story had been years ago and the facts had changed, because pursuing an update of an old story was frequently framed as some kind of insult to the reporter who’d done it before. Many sharp ideas just hit a wall of silence.

And to be fair, some of that did seem politically motivated, before and after Trump was elected. I remember resistance to covering the violent MS-13 gang after it became a major talking point in Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric—even though the gang was active and murdering people in communities around the D.C. metropolitan area, close to NPR’s headquarters, and just miles from where many staffers lived. I think a lot of critics would consider that “wokeness”: pussyfooting around an issue because it might offend people of color. I saw it as low-key racial bias, because MS-13’s victims were mostly poor Central American immigrants, the kind of people we didn’t think our affluent white listenership would pay attention to.

Race has long been one of those third-rail issues in NPR’s coverage. I was part of the Code Switch team, beginning in August 2014, around the time that Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson. The Code Switch unit had been birthed in one of those fits of diversity enthusiasm that have dotted the organization’s timeline from my first years there. The unit started in 2013, in the age of Obama, and focused mainly on blogging about race and the intersection with culture. But that changed when the network shut down Tell Me More with Michel Martin, a show that made covering race a priority, and one that I worked on from its first weeks until the bitter end. Code Switch stepped into the gap, with strong but soul-crushing coverage of police brutality, racist violence, protests, and civil unrest.

NPR did excellent work in covering those stories, including Michel—who is a mentor and dear friend to me—leading a community forum from Missouri, and great investigative reporting on a culture of corruption in Ferguson that led to overpolicing of Black residents.

Some listeners rightly pointed out that police killed white people too, and often under shady circumstances. When I suggested that we pursue it as a story, I got crickets. When video emerged of a cop shooting white teenager Zachary Hammond during a drug sting operation, I couldn’t get our leadership to green-light reporting on it. Code Switch was the only unit that went to air with something on Hammond’s death. I think that’s because it would have complicated—or acknowledged the complication—of a story where we could smugly position ourselves as on the “right” side.

And that’s what the core editorial problem at NPR is and, frankly, has long been: an abundance of caution that often crossed the border to cowardice. NPR culture encouraged an editorial fixation on finding the exact middle point of the elite political and social thought, planting a flag there, and calling it objectivity. That would more than explain the lack of follow-up on Hunter Biden’s laptop and the lab-leak theory, going full white guilt after George Floyd’s murder, and shifting to indignant white impatience with racial justice now.

Layers of complex relationships made genuine editorial criticism hazardous at NPR. Even in an industry in which office romances happen a lot, NPR has been exceptional, boasting dozens of “met and married” couples. And that doesn’t cover all the quiet couples, besties, and other personal entanglements. All this means that if you criticized someone’s editorial decisions in a meeting, their best friend, sweetheart, or ex might be glowering at you from across the table. Even a mild critique could be met with: You know John’s been having a hard time because his dad just died/wife just left him/kid is having problems. Give him a break. Lots of people who were in relationships with colleagues kept it out of their work, but enough did not that it contributed to a culture where whisper networks replaced open discussion.

Given all that, I have to acknowledge that I understand how Uri could’ve been honestly mistaken in reaching some of his conclusions. Another chronic organizational struggle at NPR is stove-piping. Your experience could be completely different from that of someone working right across the hall from you, depending on the team you worked with and the meetings you went to. I was lucky, and (mostly) played my cards right during my years there. I landed with great groups of journalists who nurtured my talents and helped me address my flaws. I loved the place and for years defended it from charges of bias, even when my friends were victims of it. I completely bought the “bad apples” version of NPR’s long-standing issues with racism and sexism.

I leaned on the positive, and the belief that NPR was great and could be better. So I was a part of a lot of the “Let’s make this diversity thing work” efforts that rankled Uri. I remember leading one session he attended, when he spoke out to insist that NPR’s diversity problem had a lot to do with issues beyond race, like class, region, education, and political perspective. He was right, and I told him so.

But maybe the stove-piping meant that Uri didn’t see the pattern in those efforts that started wearing my spirit down. Some big news in the world or an internal failure would spark a wave of carefully stage-managed soul-searching from leadership, and ad hoc committees of well-intentioned volunteers would be assembled to write lists of recommendations. Then those recommendations would be politely received, filed away, and forgotten. And two or three years later, some new crisis would start the cycle all over again. In my experience, those multihyphenate identity groups or task forces were disproportionately full of junior staffers. Because many veterans—except for true-believing tryhards like me—understood that they were a waste of time.

One of the moments that sealed my decision to leave NPR was a conversation with my colleague and friend Keith Woods, NPR’s chief diversity officer. I was struck by a profound sense of déjà vu, not just about the stubborn challenge of diversifying NPR’s coverage. I felt that he and I were repeating—word for word, beat for beat—a discussion about source diversity that we’d had in the exact same room years before.

By that time, my rose-colored glasses and NPR-fueled sense of my own superior powers of understanding had already taken a severe beating. I had thought highly of all the men who were later felled by the sexual harassment scandal and had unwittingly recommended some of them as mentors to young journalists. I discovered that Mike Oreskes—someone whom I trusted and who was critical in helping me get back into NPR in 2017—had even harassed one of the women I encouraged to seek him out for career advice. I was stunned in the management-level meetings and conversations where harassment victims were disparaged as troublemakers, and harassers who were still with the company were protected.

I so loved the version of NPR that I had experienced and had amplified in my imagination that I was slow to see the cruelty being done to people I worked with and cared about. Because of my reputation in the system, I had become a magnet for young public radio journalists across the country who wanted to share their stories of being sexually or racially harassed, underpaid, or bullied, and ask for my advice. I lost track of how many of these calls I got, or how many discreet coffeehouse chats revealed a new story of abuse. I remember at least three people who told me some version of “It’s OK. I don’t think about killing myself anymore.” For what it’s worth, two of those were young white journalists. When I reached out to talk with a wise NPR connected elder about it, her advice was to stop taking those calls. Pretend that I didn’t know the facts, because they challenged the narrative about who we were, and how my hubris had contributed to it.

I guess that’s why I think Uri is most wrong about NPR’s relationship with the rest of the country. It’s a very accurate reflection of America right now, a place where people won’t admit that good intentions don’t always yield good results, and would rather hide behind the myth of its excellence than do the hard work of making it a reality. I sincerely hope there’s still time to turn it around.

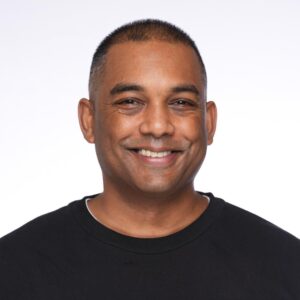

Omkhar Arasaratnam is the General Manager of the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF). He is a veteran cybersecurity and technical risk management executive with more than 25 years of experience leading global organizations. Omkhar began his career as a strong supporter of open source software as a PPC64 maintainer for Gentoo and contributor to the Linux kernel, and that enthusiasm for OSS continues today. Before joining the OpenSSF, he led security and engineering organizations at financial and technology institutions, such as Google, JPMorgan Chase, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, TD Bank Group, and IBM. As a seasoned technology leader, he has revolutionized the effectiveness of secure software engineering, compliance, and cybersecurity controls. He is also an accomplished author and has led contributions to many international standards. Omkhar is also a NYU Cyber Fellow Advisory Council member and a Senior Fellow with the NYU Center for Cybersecurity where he guest lectures Applied Cryptography.

Omkhar Arasaratnam is the General Manager of the Open Source Security Foundation (OpenSSF). He is a veteran cybersecurity and technical risk management executive with more than 25 years of experience leading global organizations. Omkhar began his career as a strong supporter of open source software as a PPC64 maintainer for Gentoo and contributor to the Linux kernel, and that enthusiasm for OSS continues today. Before joining the OpenSSF, he led security and engineering organizations at financial and technology institutions, such as Google, JPMorgan Chase, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, TD Bank Group, and IBM. As a seasoned technology leader, he has revolutionized the effectiveness of secure software engineering, compliance, and cybersecurity controls. He is also an accomplished author and has led contributions to many international standards. Omkhar is also a NYU Cyber Fellow Advisory Council member and a Senior Fellow with the NYU Center for Cybersecurity where he guest lectures Applied Cryptography.