The cargo cult metaphor is commonly used by programmers.

This metaphor was popularized by Richard Feynman's

"cargo cult science" talk with a vivid description of South Seas cargo cults.

However, this metaphor has three major problems.

First, the pop-culture depiction of cargo cults is inaccurate and fictionalized, as I'll show.

Second, the metaphor is overused and has contradictory meanings making it a lazy insult.

Finally, cargo cults are portrayed as an amusing story of native misunderstanding but the background is much darker:

cargo cults are a reaction to decades of oppression of Melanesian islanders and the destruction of their

culture.

For these reasons, the cargo cult metaphor is best avoided.

In this post, I'll describe some cargo cults from 1919 to the present. These cargo cults are

completely different from

the description of cargo cults you usually find on the internet, which I'll call

the "pop-culture cargo cult."

Cargo cults are extremely diverse, to the extent that anthropologists disagree on the cause, definition, or even

if the term has value.

I'll show that many of the popular views of cargo cults come from a 1962 "shockumentary" called Mondo Cane.

Moreover, most online photos of cargo cults are fake.

Feynman and Cargo Cult Science

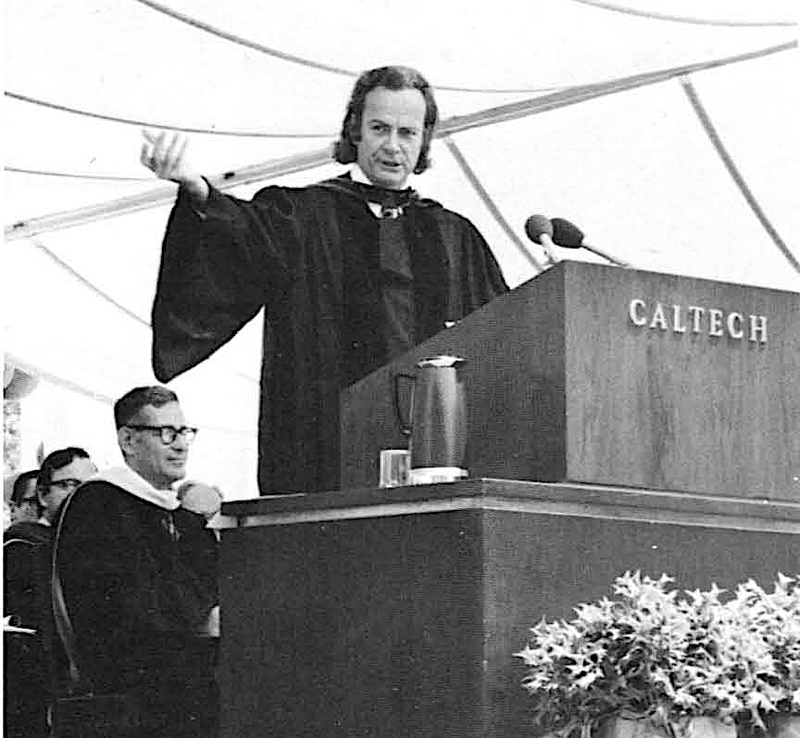

The cargo cult metaphor in science started with Professor Richard Feynman's well-known 1974

commencement address at Caltech.1

This speech, titled "Cargo Cult Science",

was expanded into a chapter in his best-selling 1985 book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman".

He said:

In the South Seas there is a cargo cult of people.

During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now.

So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land.

They’re doing everything right.

The form is perfect.

It looks exactly the way it looked before.

But it doesn’t work.

No airplanes land.

So I call these things cargo cult science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

Richard Feynman giving the 1974 commencement address at Caltech. Photo from

Wikimedia Commons.

But the standard anthropological definition of "cargo cult" is entirely different: 2

Cargo cults are strange religious movements in the South Pacific that appeared during the last few decades.

In these movements, a prophet announces the imminence of the end of the world in a cataclysm which will destroy everything.

Then the ancestors will return, or God, or some other liberating power, will appear, bringing all the goods the people desire, and ushering in a reign of eternal bliss.

An anthropology encyclopedia gives a similar definition:

A southwest Pacific example of messianic or millenarian movements once common throughout the colonial world, the modal cargo cult was an agitation or organised social movement of Melanesian villagers in pursuit of ‘cargo’ by means of renewed or invented ritual action that they hoped would induce ancestral spirits or other powerful beings to provide.

Typically, an inspired prophet with messages from those spirits persuaded a community that social harmony and engagement in improvised ritual (dancing, marching, flag-raising) or revived cultural traditions would, for believers, bring them cargo.

As you may see, the pop-culture explanation of a cargo cult and the anthropological definition are

completely different, apart from the presence of "cargo" of some sort.

Have anthropologists buried cargo cults under layers of theory? Are they even discussing

the same thing?

My conclusion, after researching many primary sources, is that the anthropological description

accurately describes the wide variety of cargo cults.

The pop-culture cargo cult description, however, takes

features of some cargo cults (the occasional runway) and combines this with movie scenes to yield an inaccurate

and fictionalized dscription.

It may be hard to believe that the description of cargo cults that you see on the internet is mostly wrong, but

in the remainder of this article, I will explain this in detail.

Background on Melanesia

Cargo cults occur in a specific region of the South Pacific called

Melanesia.

I'll give a brief (oversimplified) description of Melanesia to provide important background.

The Pacific Ocean islands are divided into three cultural areas:

Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia.

Polynesia is the best known, including Hawaii, New Zealand, and Samoa.

Micronesia, in the northwest, consists of thousands of small islands, of which Guam is the largest;

the name "Micronesia" is Greek for "small island".

Melanesia, the relevant area for this article, is a group of islands between Micronesia and Australia, including

Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, and New Guinea.

(New Guinea is the world's second-largest island; confusingly, the country of Papua New Guinea occupies the eastern half

of the island, while the western half is part of Indonesia.)

The inhabitants of Melanesia typically lived in small villages of under 200 people, isolated by mountainous geography.

They had a simple, subsistence economy, living off cultivated root vegetables, pigs, and hunting.

People tended their own garden, without specialization

into particular tasks.

The people of Melanesia are dark-skinned, which will be important ("Melanesia" and "melanin" have the same root).

Technologically, the Melanesians used stone, wood, and shell tools, without knowledge

of metallurgy or even weaving.

The Melanesian cultures were generally violent3 with everpresent tribal warfare and cannibalism.4

Due to the geographic separation of tribes, New Guinea became the most linguistically diverse

country in the world, with over 800 distinct languages.

Pidgin English was often the only way for tribes to communicate, and is now one of the

official languages of New Guinea.

This language, called Tok Pisin (i.e. "talk pidgin"),

is now the most common language in Papua New Guinea, spoken by over two-thirds of the population.5

For the Melanesians, religion was a matter of ritual, rather than a moral framework.

It is said that "to the Melanesian, a religion is above all a technology: it is the knowledge of how to bring the community into the correct relation, by rites and spells, with the divinities and spirit-beings and cosmic forces that can make or mar man's this-worldly wealth and well-being."

This is important since, as will be seen, the Melanesians expected that the correct ritual

would result in the arrival of cargo.

Catholic and Protestant missionaries converted the inhabitants to Christianity,

largely wiping out traditional religious practices and customs;

Melanesia is now over 95% Christian.

Christianity played a large role in cargo cults, as will be shown below.

European explorers first reached Melanesia in the 1500s, followed by colonization.6

By the end of the 1800s, control of the island of New Guinea was divided among Germany, Britain, and the Netherlands.

Britain passed responsibility to Australia

in 1906 and Australia gained the German part of New Guinea in World War I.

As for the islands of Vanuatu, the British and French colonized them (under the name New Hebrides) in the 18th century.

The influx of Europeans was highly harmful to the Melanesians.

"Native society was severely disrupted by war, by catastrophic epidemics of European diseases, by the introduction of alcohol, by the devastation of generations of warfare, and by the depredations of the labour recruiters."8

People were kidnapped and forced to work as laborers in other countries, a practice called blackbirding. Prime agricultural land was taken by planters to raise crops such as coconuts for export, with natives

coerced into working for the planters.9

Up until 1919, employers were free to flog the natives for disobedience; afterward,

flogging was technically forbidden but still took place. Colonial administrators jailed natives who stepped out of line.7

Cargo cults before World War II

While the pop-culture cargo cults explains them as a reaction to World War II, cargo cults started years earlier.

One anthropologist stated, "Cargo cults long preceded [World War II], continued to occur during the war, and have continued to the present."

The first writings about cargo cult behavior date back to 1919, when it was called the "Vailala Madness":10

The natives were saying that the spirits of their ancestors had appeared to several in the villages and told them that all

flour, rice, tobacco, and other trade belonged to the New Guinea people,

and that the white man had no right whatever to these goods;

in a short time all the white men were to be driven away, and then everything would be in the hands of the natives;

a large ship was also shortly to appear bringing back the spirits of their departed relatives with quantities of cargo, and all the villages were to make ready to receive them.

The 1926 book In Unknown New Guinea

also describes the Vialala Madness:11

[The leader proclaimed]

that the ancestors were coming back in the persons of the white people in the country and that all the things introduced by the white people and the ships that brought them belonged really to their ancestors and themselves.

[He claimed that] he himself was King George and his friend was the Governor.

Christ had given him this authority and he was in communication with Christ

through a hole near his village.

The Melanesians blamed the Europeans for the failure of cargo to arrive.

In the 1930s, one story was

that because the natives had converted to Christianity, God was sending the ancestors with cargo that was loaded on

ships. However, the Europeans were going through the cargo holds and replacing the names on the crates so

the cargo was fraudulently delivered to the Europeans instead of the rightful natives.

The Mambu Movement occurred in 1937.

Mambu, the movement's prophet, claimed that "the Whites had deceived the natives.

The ancestors lived inside a volcano on Manum Island, where they worked hard

making goods for their descendants: loin-cloths, socks, metal axes, bush-knives,

flashlights, mirrors, red dye, etc., even plank-houses, but the scoundrelly Whites

took the cargoes.

Now this was to stop. The ancestors themselves would bring the goods in a large ship."

To stop this movement, the Government arrested Mambu, exiled him, and imprisoned him for six months in 1938.

To summarize, these early cargo cults believed that ships would bring cargo that rightfully belonged to the natives but

had been stolen by the whites. The return of the cargo would be accompanied by the spirits of the ancestors.

Moreover, Christianity often played a large role.

A significant racial component was present, with natives driving out the whites or becoming white themselves.

Cargo cults in World War II and beyond

World War II caused tremendous social and economic upheavals in Melanesia.

Much of Melanesia was occupied by Japan near the beginning of the war and

the Japanese treated the inhabitants harshly.

The American entry into the war led to heavy conflict in the area such as the

arduous New Guinea campaign

(1942-1945) and

the Solomon Islands campaign.

As the Americans and Japanese battled for control of the islands, the inhabitants were caught in the middle.

Papua and New Guinea suffered over 15,000 civilian deaths, a shockingly high number for such a small region.12

The photo shows a long line of F4F Wildcats at Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, April 14, 1943.

Solomon Islands was home to several cargo cults, both before and after World War II (see

map).

Source:

US Navy photo 80-G-41099.

The impact of the Japanese occupation on cargo cults is usually ignored.

One example from 1942 is a cargo belief that the Japanese soldiers

were spirits of the dead, who were being sent by Jesus to liberate the people from European rule.

The Japanese would bring the cargo by airplane since

the Europeans were blocking the delivery of cargo by ship.

This would be accompanied by storms and earthquakes, and the natives' skin would change from

black to white.

The natives were to build storehouses for the cargo and fill the storehouses with food for

the ancestors.

The leader of this movement, named Tagarab,

explained that he had an iron rod that gave him messages

about the future.

Eventually, the Japanese shot Tagarab, bringing an end to this cargo cult.13

The largest and most enduring cargo cult is the John Frum movement, which started

on the island of Tanna around 1941 and continues to the present.

According to one story, a mythical person known as John Frum, master of the airplanes, would reveal himself and

drive off the whites.

He would provide houses, clothes, and food for the people of Tanna.

The island of Tanna would flatten as the mountains filled up the valleys and everyone

would have perfect health.

In other areas, the followers of John Frum believed they "would receive a great quantity

of goods, brought by a white steamer which would come from America."

Families abandoned the Christian villages and moved to primitive shelters in the interior.

They wildly spent much of their money and threw the rest into the sea.

The government arrested and deported the leaders, but that failed to stop the movement.

The identity of John Frum is unclear; he is sometimes said to be a white American while in other cases natives have claimed to be John Frum.14

The cargo cult of Kainantu17 arose around 1945 when a

"spirit wind" caused people in the area to shiver and shake.

Villages built large "cargo houses" and put stones, wood, and insect-marked leaves inside,

representing European goods, rifles, and paper letters respectively.

They killed pigs and anointed the objects, the house, and themselves with blood.

The cargo house was to receive the visiting European spirit of the dead who would fill

the house with goods.

This cargo cult continued for about 5 years, diminishing as people became

disillusioned by the failure of the goods to arrive.

The name "Cargo Cult" was first used in print in 1945, just after the end of World War II.15

The article blamed the problems on the teachings of missionaries, with the problems "accentuated a hundredfold" by World War II.

Stemming directly from religious teaching of equality, and its resulting sense of injustice, is what is generally known as “Vailala Madness,” or “Cargo Cult.” "In all cases the "Madness" takes the same form: A native, infected with the disorder, states that he has been visited by a relative long dead, who stated that a great number of ships loaded with "cargo" had been

sent by the ancestor of the native for the benefit of the natives of a particular village

or area.

But the white man, being very cunning, knows how to intercept these ships and

takes the "cargo" for his own use...

Livestock has been destroyed, and gardens neglected in the expectation of the

magic cargo arriving. The natives infected by the "Madness" sank into indolence and apathy

regarding common hygiene."

In a 1946 episode, agents of the Australian government found a group of New Guinea

highlanders who believed that the arrival of the whites signaled that the end of the world

was at hand.

The highlanders butchered all their pigs in the expectation that "Great Pigs" would appear from

the sky in three days. At this time, the residents would exchange their black skin for white skin.

They created mock radio antennas of bamboo and rope to receive news of the millennium.16

The New York Times described Cargo Cults in 1948 as "the belief that a convoy of cargo

ships is on its way, laden with the fruits of the modern world, to outfit the leaf

huts of the natives."

The occupants of the British Solomon Islands were building

warehouses along the beaches to hold these goods.

Natives marched into a US Army camp, presented $3000 in

US money, and asked the Army to drive out the British.

A 1951 paper described cargo cults:

"The insistence that a 'cargo' of European goods is to be sent by the ancestors

or deceased spirits; this may or may not be part of a general reaction

against Europeans, with an overtly expressed desire to be free from alien domination.

Usually the underlying theme is a belief that all trade goods were sent by ancestors

or spirits as gifts for their descendants, but have been misappropriated on the

way by Europeans."17

In 1959, The New York Times wrote about cargo cults: "Rare Disease and Strange Cult Disturb New Guinea Territory; Fatal Laughing Sickness Is Under Study by Medical Experts—Prophets Stir Delusions of Food Arrivals".

The article states that "large native groups had been

infected with the idea that they could expect the arrival of spirit ships carrying large supplies of food.

In false anticipation of the arrival of the 'cargoes', 5000 to 7000 native have been known to consume their entire food reserve and create a famine."

As for "laughing sickness", this is now known to be a prion disease transmitted by eating human brains.

In some communities, this disease, also called Kuru, caused 50% of all deaths.

A detailed 1959 article in Scientific American, "Cargo Cults", described many

different cargo cults.16

It lists various features of cargo cults, such as the return of the dead, skin color switching from black to

white, threats against white rule, and belief in a coming messiah.

The article finds a central theme in cargo cults: "The world is about to end in a terrible cataclysm. Thereafter God, the ancestors or some local culture hero will appear and inaugurate a blissful paradise on earth. Death, old age, illness and evil will be unknown. The riches of the white man will accrue to the Melanesians."

In 1960, the celebrated naturalist David Attenborough created a documentary

The People of Paradise: Cargo Cult.18

Attenborough travels through the island of Tanna and encounters many artifacts of the John Frum cult,

such as symbolic gates and crosses, painted brilliant scarlet and decorated with objects such as a shaving brush,

a winged rat, and a small carved airplane.

Attenborough interviews a cult leader who

claims to have talked with the mythical John Frum, said to be a white American.

The leader remains in communication with John Frum through a tall pole said to

be a radio mast, and an unseen radio.

(The "radio" consisted of an old woman with electrical wire wrapper around her

waist, who would speak gibberish in a trance.)

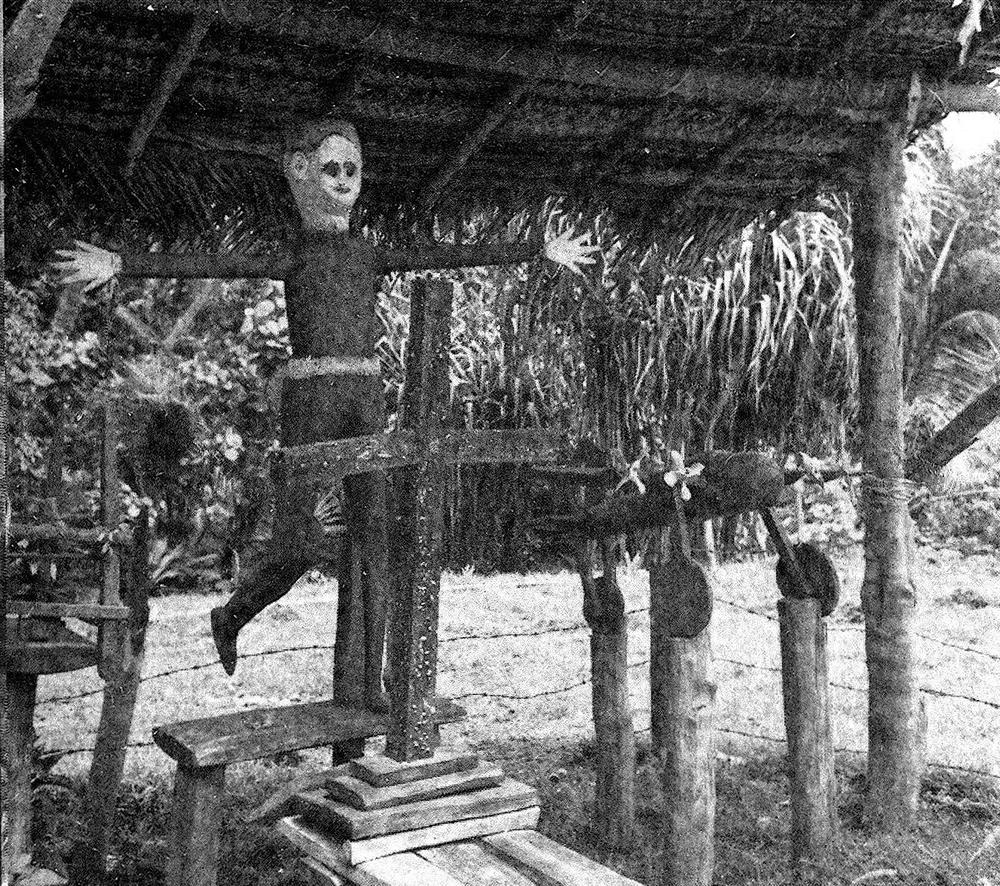

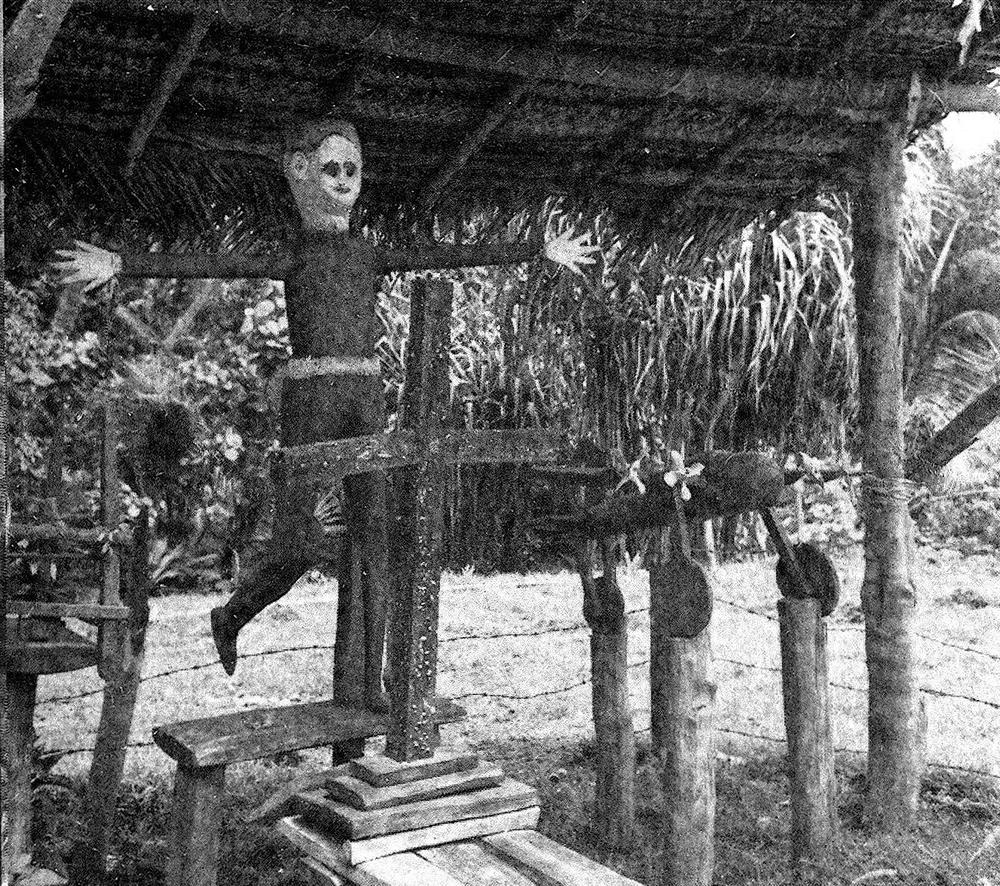

"Symbols of the cargo cult." In the center, a representation of John Frum with "scarlet coat and a white European face" stands behind a brilliantly painted cross. A wooden airplane is on the right, while on the left (outside the photo) a cage contains a winged rat. From

Journeys to the Past, which describes Attenborough's visit to the island of Tanna.

In 1963, famed anthropologist Margaret Mead brought cargo cults to the general public, writing Where Americans are Gods: The Strange Story of the Cargo Cults in the mass-market

newspaper supplement Family Weekly.

In just over a page, this article describes the history of

cargo cults before, during, and after World War II.19

One cult sat around a table with vases of colorful flowers on them.

Another cult threw away their money.

Another cult watched for ships from hilltops, expecting John Frum to bring a

fleet of ships bearing cargo from the land of the dead.

One of the strangest cargo cults was a group of 2000 people on New Hanover Island,

"collecting money to buy President Johnson of the United States [who] would arrive with other Americans on the liner Queen Mary and helicopters next Tuesday."

The islanders raised $2000, expecting American cargo to follow the president.

Seeing the name Johnson on outboard motors confirmed their belief

that President Johnson was personally sending cargo.20

A 1971 article in Time Magazine22 described how tribesmen brought US Army concrete survey markers down from a mountaintop

while reciting the Roman Catholic rosary, dropping the heavy markers

outside the Australian government office.

They expected that "a fleet of 500 jet transports would disgorge thousands of sympathetic Americans

bearing crates of knives, steel axes, rifles, mirrors and other wonders."

Time magazine explained the “cargo cult” as "a conviction that if only the dark-skinned people can hit on the magic formula, they can, without working, acquire all the wealth and possessions that seem concentrated in the white world...

They believe that everything has a deity who has to be contacted through ritual and who only then will deliver the cargo."

Cult leaders tried

"to duplicate the white man’s magic. They hacked airstrips in the rain forest, but no planes came. They built structures that look like white men’s banks, but no money materialized."21

National Geographic, in an article Head-hunters in Today's World (1972),

mentioned a cargo-cult landing field with a replica of a radio aerial, created by villagers who hoped that it would attract airplanes bearing gifts.

It also described a cult leader in South Papua who claimed to obtain airplanes and cans of food from a hole in the ground.

If the people believed in him, their skins would turn white and he would lead them to freedom.

These sources and many others23 illustrate that cargo cults do not fit a simple story.

Instead, cargo cults are extremely varied, happening across thousands of miles and many decades.

The lack of common features between cargo cults leads some

anthropologists to reject the idea of cargo cults as a meaningful term.24

In any case, most historical cargo cults have very little in common with the pop-culture description of a cargo cult.

Cargo beliefs were inspired by Christianity

Cargo cult beliefs are closely tied to Christianity, a factor that is ignored in pop-culture descriptions of

cargo cults.

Beginning in the mid-1800s, Christian missionaries set up churches in New Guinea to convert the inhabitants.

As a result, cargo cults incorporated Christian ideas, but in very confusing ways.

At first, the natives believed that missionaries had come to reveal the ritual secrets and restore

the cargo.

By enthusiastically joining the church, singing the hymns, and following the church's rituals,

the people would be blessed by God, who would give them the cargo.

This belief was common in the 1920s and 1930s, but as the years went on and the people didn't

receive the cargo,

they theorized that the missionaries had removed the first pages of the Bible to hide

the cargo secrets.

A typical belief

was that God created Adam and Eve in Paradise, "giving them cargo:

tinned meat, steel tools, rice in bags, tobacco in tins, and matches, but not cotton clothing."

When Adam and Eve offended God by having sexual intercourse, God threw them out of Paradise

and took their cargo.

Eventually, God sent the Flood but Noah was saved in a steamship and God gave back the cargo.

Noah's son Ham offended God, so God took the cargo away from Ham and sent him to New Guinea,

where he became the ancestor of the natives.

Other natives believed that God lived in Heaven, which was in the clouds and reachable by ladder from Sydney, Australia

(source).

God, along with the ancestors, created cargo in Heaven—"tinned meat, bags of rice, steel tools, cotton cloth, tinned tobacco, and

a machine for making electric light"—which would be flown from Sydney and delivered to the natives, who thus needed to

clear an airstrip (source).25

Another common belief was that symbolic radios could be used to communicate with Jesus.

For instance, a Markham Valley cargo group in 1943 created large radio houses so they could be informed of the imminent Coming of Jesus, at which point

the natives would expel the whites (source).

The "radio" consisted of bamboo cylinders connected to a rope "aerial" strung between two poles. The houses contained a pole with

rungs so the natives could climb to Jesus along with cane "flashlights" to see Jesus.

A tall mast with a flag and cross on top. This was claimed to be a special radio mast that enabled

communication with John Frum. It was decorated with scarlet leaves and flowers.

From Attenborough's

Cargo Cult.

Mock radio antennas are also discussed in a 1943 report26 from a wartime patrol that

found a bamboo "wireless house", 42 feet in diameter.

It had two long poles outside and with an "aerial" of rope between them, connected to

the "radio" inside, a bamboo cylinder.

Villagers explained that the "radio" was to receive messages of the return of Jesus,

who would provide weapons for the overthrow of white rule.

The villagers constructed ladders outside the house so they could climb up to the Christian

God after death.

They would shed their skin like a snake, getting a new white skin, and then they would

receive the "boats and white men's clothing, goods, etc."

Mondo Cane and the creation of the pop-culture cargo cult

As described above, cargo cults expected the cargo to arrive by ships much more often than airplanes.

So why do pop-culture cargo cults have detailed descriptions of runways, airplanes, wooden headphones, and bamboo control towers?27

My hypothesis is that it came from a 1962 movie called Mondo Cane.

This film was the first "shockumentary", showing extreme and shocking scenes from around the world.

Although the film was highly controversial, it was shown at the Cannes Film Festival and was a box-office success.

The film made extensive use of New Guinea with multiple scandalous segments, such as a group of "love-struck" topless women chasing men,29 a

woman breastfeeding a pig, and women in cages being fattened for marriage.

The last segment in the movie showed

"the cult of the cargo plane":

natives forlornly watching planes at the airport, followed by scenes of a bamboo airplane sitting on a mountaintop "runway"

along with bamboo control towers. The natives waited all day and then lit torches to illuminate the runway at nightfall.

These scenes are very similar to the pop-culture descriptions of cargo cults so I suspect this movie is the

source.

A still from the 1962 movie "

Mondo Cane", showing a bamboo airplane sitting on a runway, with flaming torches acting as beacons. I have my doubts about its accuracy.

The film claims that all the scenes "are true and taken only from life", but many of the scenes are said to be staged.

Since the cargo cult scenes are very different from anthropological reports and much more dramatic, I

think they were also staged and exaggerated.28

It is known that the makers of Mondo Cane paid the Melanesian natives generously for the filming (source, source).

Did Feynman get his cargo cult ideas from Mondo Cane?

It may seem implausible since the movie was released over a decade earlier.

However, the movie became a cult classic, was periodically shown in theaters, and influenced academics.30

In particular, Mondo Cane showed at the famed Cameo theater in downtown Los Angeles on April 3, 1974, two months before Feynman's commencement speech.

Mondo Cane seems like the type of offbeat movie that Feynman would see and the theater was just 11 miles from Caltech.

While I can't prove that Feynman went to the showing, his description of a cargo cult strongly resembles the movie.31

Fake cargo-cult photos fill the internet

Fakes and hoaxes make researching cargo cults online difficult.

There are numerous photos online of cargo cults, but many of these photos are completely

made up.

For instance, the photo below has illustrated cargo cults for articles such as Cargo Cult, UX personas are useless, A word on cargo cults,

The UK Integrated Review and security sector innovation,

and Don't be a cargo cult.

However, this photo is from a Japanese straw festival and has nothing to do with cargo cults.

An airplane built from straw, one creation at a Japanese straw festival. I've labeled the photo with "Not cargo cult" to ensure it doesn't get reused in cargo cult articles.

Another example is the photo below, supposedly an antenna created by a cargo cult.

However, it is actually

a replica of the Jodrell Bank radio telescope,

built in 2007 by a British farmer from six tons of straw

(details).

The farmer's replica ended up erroneously illustrating

Cargo Cult Politics,

The Cargo Cult & Beliefs,

The Cargo Cult,

Cargo Cults of the South Pacific,

and

Cargo Cult, among others.32

Other articles illustrate cargo cults with the aircraft below, suspiciously

sleek and well-constructed.

However, the photo actually shows a wooden wind tunnel model of the Buran spacecraft,

abandoned at a Russian airfield as described in this article.

Some uses of the photo are Are you guilty of “cargo cult” thinking without even knowing it? and

The Cargo Cult of Wealth.

This is an abandoned Soviet wind tunnel model of the Buran spacecraft. Photo by Aleksandr Markin.

Many cargo cult articles use one of the photo below. I tracked them down to the 1970 movie "Chariots of the Gods" (link),

a dubious documentary claiming that aliens have visited Earth throughout history.

The segment on cargo cults is similar to Mondo Cane with cultists surrounding a mock plane on a mountaintop,

lighting fires along the runway.

However, it is clearly faked, probably in Africa: the people don't look like Pacific Islanders and are wearing

wigs. One participant wears leopard skin (leopards don't live in the South Pacific).

The vegetation is another giveaway: the plants are from

Africa, not the South Pacific.33

Two photos of a straw plane from "Chariots of the Gods".

The point is that most of the images that illustrate cargo cults online are fake or

wrong. Most internet photos and information about cargo cults have just been copied from page to page.

(And now we have AI-generated cargo cult photos.)

If a photo doesn't have a clear source (including who, when, and where), don't believe it.

Conclusions

The cargo cult metaphor should be avoided for three reasons.

First, the metaphor is essentially meaningless and heavily overused.

The influential "Jargon File" defined cargo-cult programming as "A style of (incompetent) programming

dominated by ritual inclusion of code or program structures that

serve no real purpose."34

Note that the metaphor in cargo-cult programming is the opposite of the metaphor in cargo-cult science:

Feyman's cargo-cult science has no chance of

working, while cargo-cult programming works but isn't understood.

Moreover, both metaphors differ from the cargo-cult metaphor in other contexts, referring to the expectation of receiving

valuables without working.35

The popular site Hacker News is an example of how "cargo cult" can be applied to anything:

agile programming,

artificial intelligence,

cleaning your desk.

Go,

hatred of Perl,

key rotation,

layoffs,

MBA programs,

microservices,

new drugs,

quantum computing,

static linking,

test-driven development, and

updating the copyright year are just a few things that are called "cargo cult".36

At this point, cargo cult is simply a lazy, meaningless attack.

The second problem with "cargo cult" is that the pop-culture description of cargo cults is historically

inaccurate.

Actual cargo cults are much more complex and include a much wider (and stranger) variety of behaviors.

Cargo cults started before World War II and involve ships more often

than airplanes.

Cargo cults mix aspects of paganism and Christianity, often with apocalyptic ideas of the end of the

current era, the overthrow of white rule, and the return of dead ancestors.

The pop-culture description discards all this complexity, replacing it with a myth.

Finally, the cargo cult metaphor turns decades of harmful colonialism into a humorous anecdote.

Feynman's description of cargo cults strips out the moral complexity:

US soldiers show up with their cargo and planes, the indigenous

residents amusingly misunderstand the situation, and everyone carries on.

However, cargo cults really were

a response to decades of colonial mistreatment, exploitation, and cultural destruction.

Moreover, cargo cults were often harmful: expecting a bounty of cargo, villagers would throw away their money,

kill their pigs, and stop tending their crops, resulting in famine.

The pop-culture cargo cult erases the decades of colonial oppression, along with the cultural upheaval

and deaths from World War II.

Melanesians deserve to be more than the punch line in a cargo cult story.

Thus, it's time to move beyond the cargo cult metaphor.

Update: well, this sparked much more discussion on Hacker News than I expected. To answer some questions: Am I better or more virtuous than other people? No. Are you a bad person if you use the cargo cult metaphor? No. Is "cargo cult" one of many Hacker News comments that I'm tired of seeing? Yes (details). Am I criticizing Feynman? No. Do the Melanesians care about this? Probably not. Did I put way too much research into this? Yes. Is criticizing colonialism in the early 20th century woke? I have no response to that.

Notes and references